The Most Profound Theorem in Logic You Haven't Heard Of

Infinity, its many models, and Löwenheim-Skolem

Is the universe countably infinite or uncountably infinite?…

I used to think language describes reality uniquely. However, Putnam showed that the Löwenheim-Skolem theorem says otherwise. Specifically, the concept of “infinity” has different meanings in different models. It’s quite abstract, but let me explain.

Firstly, what’s a “model”?

In a formal theory, it’s a set of axioms and rules (actually it’s what “satisfies” those). Examples would be set theory or arithmetic. A “model” for that theory is like a mathematical world (technically called by model-theorists a “Universe,” interestingly enough) where all those axioms and rules are true.

Some say it’s like an interpretation, but I’d say it’s more like what’s being “referred to.”

So, if you have a theory that says, “There exists an infinite set,” a model for that theory would be a mathematical structure that contains an infinite set.

Super simple so far.

The Limits of Logic

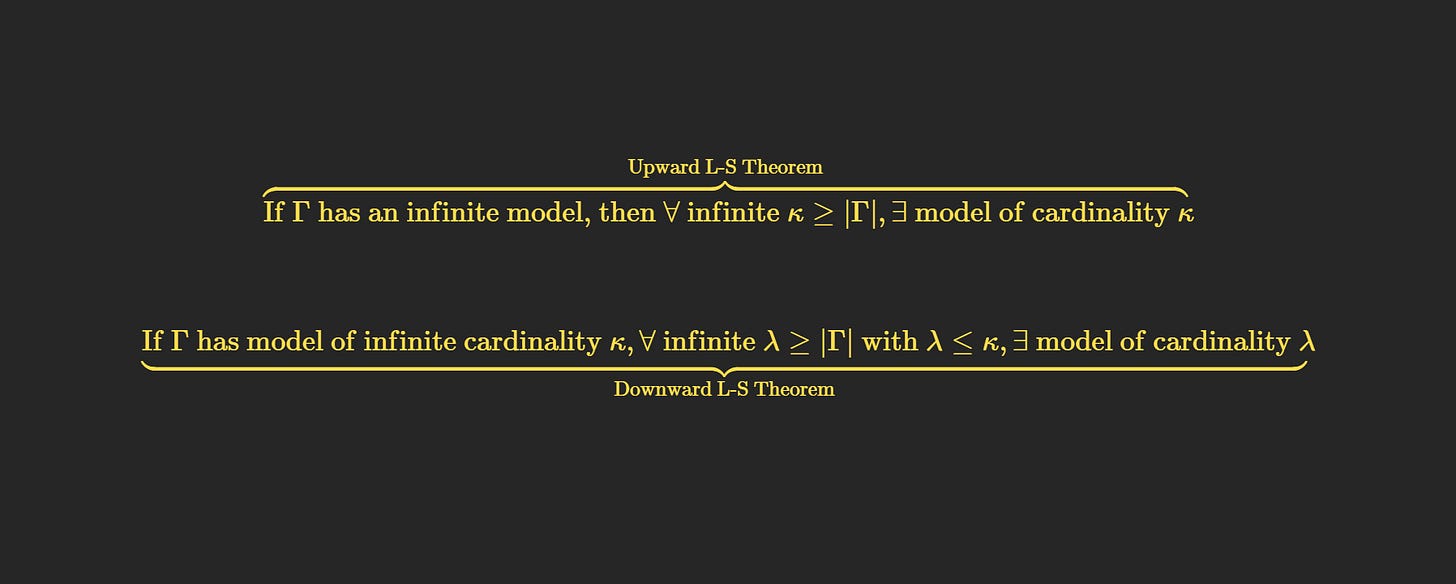

Two mathematicians, Löwenheim and Skolem, in the early 1900s (prior to Gödel) found something even more unintuitive than Incompleteness. They proved that if your first-order theory has an infinite model (a model with an infinite “universe,” recall), then it also has a countable model.

Okay, so what? So what if a theory that describes an uncountable infinity can also be interpreted in a model where everything is countable? Well, in some ways, it’s like saying anything that’s first-order logically true of uncountably infinite sets like the real or complex numbers is true of the countables like the natural numbers.

Unless you’ve studied set theory (or logic, broadly), it’s difficult to appreciate how absolutely bizarre this is.

In some ways, this means that even our best mathematical theories can’t pin down the “true” size of infinity. “Uncountable” in one model might be countable in another. The concept of infinity itself becomes slippery.

This is seen more as an apparent paradox than an actual contradiction. It’s something that mathematicians find curious but then abandon because it’s not showing “A and not A” simultaneously.

Hilary Putnam wondered, “What does this mean for reality itself? If our theories can’t distinguish between a countable and an uncountable universe, does the question even make sense? Is the size of the universe a ‘fact’ about the world, or is it just an artifact of our models?”

Putnam's Paradoxical Playground

Here’s an example. Imagine a theory that describes the real numbers. Löwenheim-Skolem says there’s a model of this theory where the “real numbers” are actually countable. But we already know the real numbers are uncountable… correct? (Cantor’s diagonal argument, for instance.)

Putnam said that this is a problem more general than just the specifics of language because he said this presents a problem for how language in general relates to reality. After all, if our theories, even our ideal theories, can’t rule out these unintended interpretations, how can we say they uniquely describe the world?

It’s tempting to think that “something else” beyond our theories fixes the true interpretation—maybe it’s our intentions or some kind of direct mental connection to the things we’re talking about (a la Penrose or Platonists). However, what could this “something else” be?

Putnam’s point is that appealing to mysterious mental powers with these unknown causal connections doesn’t solve the problem. It just pushes it back.

How do we know our intentions themselves are any less ambiguous than our theories?

You may think, “Sure, my words can be ambiguous, but my thoughts are crystal clear.” But how do you know that? How do you know that for the thoughts that are expressed through language, internal or external?

If language is ambiguous, then so are our thoughts. We can’t just magically ‘intend’ the right interpretation without some way of grounding that intention.

…Grounding, by the way, is philosopher-speak for “explaining something in terms of something more fundamental.”

Who’s Counting Anyway?

So, are we / you / I stuck? Putnam says no. His model-theoretic argument shows that metaphysical realism, which says reality has exactly one true description, collapses since even ideal theories can’t nail down a single unique reference. But he’s not an anti-realist. Instead, he says we need a type of realism that doesn’t try to totally divorce reference from our practices of verification.

This is where “non-realist” (as opposed to anti-realist) semantics comes in.

Instead of thinking of meaning in terms of truth conditions, we can think of it in terms of how we use language—the inferences we make, the observations that support our claims, etc.

On this view, the meaning of “infinity” isn’t fixed by some external reality but by how we use the concept in our mathematical practice. Different practices (formal linguistic and mathematical) may lead to different, but equally valid, notions of infinity. This sounds like anti-realism or at least relativism, but it’s not.

NOTE: It’s not saying anything goes or that everything is mind-dependent. It’s saying that meaning and truth are tied to practices and our ways of understanding the world.

There’s no “God’s eye view” that gives us the One True Interpretation. At least not one accessible by us…

Okay, to get back to it… “Is the universe countable or uncountable?”

The answer is: it depends on how you look at it. Our theories don’t give us a unique answer, and perhaps that’s okay. Perhaps the question itself needs to be reframed.

The real lesson of Löwenheim-Skolem is that the universe isn’t a mathematical object waiting around to be described. At least not mathematically or logically (or specifically, first-order logically).

The universe is something you engage with. Something you try to make sense of using the tools you have.

- Curt Jaimungal

CJ: “The universe is something you engage with. Something you try to make sense of using the tools you have.”

Great conclusion and a great quote.

Excellent stuff! This paradox is a great specific example of Map-territory relation where the saying "All models are wrong (but some are useful)" originated. You even alluded to this idea towards the end. Essentially any conceptual/mathematical/logical model is not a perfect map of reality nor will it ever be. All we can do is try to continue minimizing the discrepancies between the model and our world. Additionally when we are building something with a specific model in mind we can ensure that we are aware of the discrepancies and ensure that those discrepancies are irrelevant to what we are building. A great entrance to the rabbit hole on these ideas here: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Map%E2%80%93territory_relation